Your First Marine Aquarium

From Microcosm Aquarium Explorer

A Better Way to Simpler, Healthier, More Beautiful Marine Aquariums

An Excerpt from

The New Marine Aquarium

By Michael S. Paletta

Like a living kaleidoscope, a marine aquarium brings us face-to-face with some of nature’s most beautiful fishes and incredible undersea life forms, offering a window on a world many of us will never visit. With a daily spectacle provided by dazzling coral reef creatures, a sparkling saltwater system can be a dynamic presence in a home, office, or classroom. It can be riveting, educational, and uniquely soothing to observers of all ages—and may even become a lifelong passion for the person who creates it. Curious humans have kept sea life in small bodies of water for millennia—the ancient Romans had maritimae (small saltwater ponds) in which they housed Mediterranean invertebrates and fishes, for both viewing and fresh table fare. (There are reports of sizable moray eels being kept, sometimes in pits into which troublesome slaves could be thrown.) Nineteenth-century British gentry kept many forms of temperate tidal life, including cold-water anemones, in a variety of containers, including inverted bell jars.

The real age of marine fishkeeping, however, has very recent origins. The popularization of scuba equipment in the mid-twentieth century suddenly opened the undersea world to study and collection, and interest in marine aquariums has blossomed in the decades since. The formulation of synthetic salt mixes, allowing landlocked hobbyists to create a viable substitute for natural seawater, was a major advance of the 1950s. Growing airline connections to the island nations of the Tropics opened supply lines for marine livestock. European and North American inventors and manufacturers responded to consumer demands for better aquariums, mechanical gear, and foods.

Never before has the would-be aquarium keeper had such a breadth of choice among equipment, livestock, and aquascaping materials—ranging from lights and controllers that emulate tropical sunshine and moonlight to never-before-seen reef fishes, live colonies of stony corals, and biologically rich reef rock and coral sand.

Impossible Dreams?

Still, it is common to hear that saltwater fishes are extremely challenging—if not impossible—to maintain in home aquarium systems. As with many aquarists, I was irreversibly hooked by the brilliant colors and movements of reef fishes, and I first approached the staff of my local aquarium shop in 1980 and told them I wanted to set up a marine fish tank. Rather than warmly welcoming me into the world of marine aquariums, their first words were: “You don’t want to do saltwater . . . it’s too difficult.”

I was astonished—I had shopped there for more than 10 years as a freshwater hobbyist, and they knew that I was successfully keeping and breeding freshwater fishes. They were even buying my homebred exotic Tanganyikan Cichlid offspring. When I pressed to discover why they were trying to dissuade me, the reply was discouraging. They said that marine tanks were difficult and expensive, that they required a lot of specialized equipment, and that, despite the expense, the fishes often died after a short time.

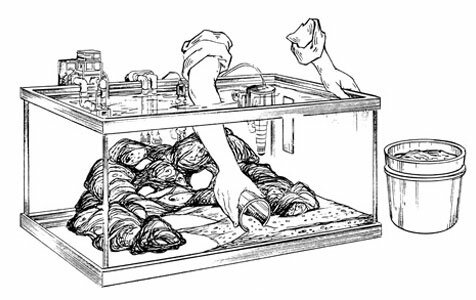

The live-rock method of setting up a new marine aquarium destined to succeed and without an undergravel filter.

The live-rock method of setting up a new marine aquarium destined to succeed and without an undergravel filter.

Undaunted, I decided to try anyway. It has now been almost 20 years since I set up that first tank. Needless to say, I was stubborn enough to prove them at least partly wrong, but along the way I did discover that some of what they said was correct. It was more expensive to set up a marine tank, not to mention how pricey the fish were and how, when anything went wrong, the most expensive specimen always seemed to be the first to go.

However, after 5 years and literally thousands of dollars I began achieving a modicum of success. My fishes were usually living for at least 6 months and I was no longer having the whole population die off mysteriously. Granted, the algae on the dead coral skeletons and glass had to be cleaned frequently, and the entire tank needed to be broken down every year or so in order for the sand and undergravel filter to be cleaned. In terms of keeping a saltwater fish tank at that time, what I was doing was messy but pretty much state of the art.

In truth, if it weren’t for the incredible beauty and fascinating behaviors of coral reef fishes and invertebrates, I probably would have given up just as so many other saltwater hobbyists did. With what we knew then, keeping a marine aquarium demanded deep pockets, a willingness to learn by experimentation, and a tremendous sense of dedication to keep going.

Reef Secrets

Then, in 1986, after seeing photographs of some European tanks, my entire perspective changed. Here were marine aquariums brimming with life—green plants, colorful live rock, and billowing soft corals—and truly starting to mimic the appearance of a coral reef. These were the first popularized “miniature-reef” tanks, where the thrust was in keeping marine invertebrates. The fishes in these tanks were scarce—almost an afterthought. Some reef aquarists even eliminated fishes altogether. These systems utilized stronger lighting and more elaborate filtration methods than anything I had ever seen, with the explanation that corals and marine invertebrates were thought to be much more difficult to maintain than fishes. Like many other aquarists, I was intrigued by the possibilities and began my own research into the new mini-reef techniques.

I’ve now been working with reef aquariums for more than a decade, and my latest home system is a 480-gallon stony coral tank with more than 100 species of live coral and a collection of fishes that includes pygmy angelfishes; fairy, flasher, and leopard wrasses; moray eels; and a mated pair of clownfish with their host anemone. In the past decade, we have seen many advances that make the keeping of these animals—once thought unkeepable—within our reach.

Filtration systems have evolved in many directions, some becoming highly complex but many others turning toward elegant simplicity. Lighting systems now do a much better job of replicating sunlight, both in terms of spectrum and intensity. In fact, there are now even small computers specifically designed to run these reef tanks (controlling pumps, lights, water chemistry, and providing constant readings on the status of the system) without the need for much intervention by their owners at all.

Most of all, marine reef aquariums are now biologically richer and their inhabitants are often able to survive for years. Among reef aquarists, it is not unusual to hear of fishes and corals living 5, 10, or even more years in captivity. Amateur aquarists are now propagating many soft and stony corals and a growing number of reef fish species. It is possible to stock a marine aquarium entirely with commercially propagated materials and specimens, including live rock, soft corals, stony corals, gorgonians, gobies, clownfishes, dottybacks, grammas, comets, cardinalfishes, giant clams, and more.

Breakthrough for Beginners

Unfortunately, the beginning hobbyist has been almost forgotten in this rush to create the ultimate reef aquarium. In terms of innovations and advice for keeping a first marine tank—usually a “fish-only” aquarium—very little has changed. An undergravel filter is still often touted as the filtration method of choice for most beginners. This equipment is available everywhere fish tanks are sold, it is cheap to acquire, and nearly a half century of use seems to have made it the unshakable standard. Those who sell them tend to believe in undergravel filters as idiot-proof and akin to training wheels for children learning to ride bikes.

However, what sort of start are we really giving these eager marine newcomers? The unfortunate answer can be found in the pet industry’s own statistics: 40 to 60% of all beginning saltwater hobbyists leave the hobby within two years of starting, despite all of the improvements in equipment, the quality of livestock, and our understanding of their needs that have been made over the last decade.

The same retail stores that steer their new marine customers to undergravel filters and the traditional bleached coral decorations that go with them will still often warn their clients that saltwater fishkeeping is difficult and expensive.

The fishes, we continue to hear, are hard to keep alive for long periods of time. These classic words of caution—the very same problems I had been warned about many years ago—are still being presented to dampen the enthusiasm of eager, would-be marine aquarists. Curiously, a very interesting development has emerged from the ongoing fascination with reef aquariums. In my own case, I began to notice that the fishes in my reef tanks were living longer and appearing healthier—an unintended by-product of changing my techniques and equipment for the keeping of corals. My tanks are now better maintained and more closely replicate a tiny portion of a reef, and the fishes are doing dramatically better as well.

Having been involved in setting up scores of saltwater systems and visiting aquarists across the country, I believe we now know enough to get new marine hobbyists off to a much better start—without all the complications and expense of setting up a full-blown reef tank. Using a better basic approach to filtration, it should now be possible to let marine fishes live out their full lifespans rather than having to replace them when they perish prematurely. Without these painful and expensive losses, fewer aquarium keepers will become discouraged and depart the hobby for other pursuits.

With this book I hope to demonstrate how to plan, equip, and establish a marine fish tank to those just coming into the saltwater hobby—as well as to anyone who has struggled or failed after using the old standard formula. The method I advocate is not revolutionary—it has been proved reliable in thousands of home aquariums—but it is seldom recommended to novices. The radical part is that it skips immediately past the undergravel filter to the live rock filtration approach that makes reef aquariums work so well.

Live Rock Method for the New Aquarist

The fundamentals of this system are:

- Live rock as the primary biological filter.

- Vigorous water circulation to promote gas exchange (including oxygenation) and efficient biological filtration.

- Nutrient export to remove wastes from the tank (by a combination of protein skimming, optional mechanical filtration, and small, regular water changes).

While an aura of mystery seems to surround it, live rock is nothing more than pieces of old coral rubble collected from shallow tropical seas on or near reefs and shipped damp to preserve the hardy organisms that cover and penetrate it. Good live rock can be festooned with life—sponges, green macroalgae, lovely calcareous algae, crustaceans, mollusks, even small corals—but at the very least, it comes loaded with beneficial microbial cultures that will help maintain healthy aquarium water.

The best live rock is irregular in shape, porous, and much more complex than a typical dense river stone. It is, in fact, more like a calcified sponge, full of nooks and crannies and impregnated with beneficial bacterial populations that can make short work of dissolved aquarium wastes.

A live rock marine setup is as simple to create as the old undergravel filter method and considerably more foolproof. Once established, it is a lower-maintenance system that can operate successfully for years without a need to tear everything down completely for cleaning. A simple arrangement of live rock makes an extremely stable biological filter, better able to facilitate the complete conversion of dissolved wastes and capable of carrying larger fish loads. I believe that fishes in a live rock system consistently live longer, act more natural, and show better colors. Even species previously considered difficult to keep or delicate will often settle into a live rock aquarium and thrive.

Filtration Pitfall

In short, we now have a simple, natural replacement for the undergravel filter. I realize that this will sound like heresy to some retail store personnel and old-time saltwater enthusiasts. Many seem to recommend the undergravel filter out of habit or familiarity—like manual typewriters and wooden downhill skis, the undergravel filter occupies an affectionate spot in some people’s hearts. It was a brilliant invention for its time.

Realistically, however, time and science have passed by these once-great examples of technology. (Ask a group of experienced marine hobbyists how many are still using undergravel filters. The answer is effectively “none.”) The undergravel filter may always be appropriate for certain freshwater and specialty marine aquariums, but as an essential piece of gear for the average new marine aquarist, it has failed to pass the test of time.

As we will discuss in the next chapter, the inescapable flaw of the undergravel filter is that it concentrates solid pollutants and becomes a hard-to-clean sink for all the undissolved wastes in the aquarium, causing a buildup of nitrate to fuel unattractive algae growth and eventually drag water quality down to unacceptably low levels. Undergravel filters are plagued by performance problems—declining circulation causes loss of filtration efficiency and even leads to the development of toxic, anaerobic areas that generate deadly hydrogen sulfide gas.

Do you, as a newcomer to marine aquariums, need to know all of this? Probably not. The important point is to understand that there is a better, simpler way—and that many saltwater fishes are no longer terribly difficult or impossible to keep. The “trick” is nothing more than starting with a system that is self-adjusting and designed for the long haul. With the simplified methods, equipment, and fish species introduced in this book, I firmly believe that the success rate for new marine hobbyists ought to rise to more than 90%, and the needless loss of fishes should decline significantly.

Costs & Benefits

The cost of live rock will cause the initial investment in a marine setup to increase beyond that of an undergravel system, but this comes with a relatively sure and quick payback. With long-term success of the live rock approach, the cost should eventually be spread out over a longer period of time. One of the highest out-of-pocket expenses of failing aquariums is the need to replace fishes that perish, and a beginner taking this new approach should be spared much of this pain. (It doesn’t take the death of too many prized specimens to add up to the additional cost of live rock that might have prevented their demise.) It’s not really the expense that pains us most, rather it is the sense that we have failed to provide adequately for our fishes’ well-being. One of the worst feelings for an aquarist is having to flush a beautiful fish down the drain—especially if better care might have saved it.

Please understand that it is not simply a matter of spending more money to be successful, as you can follow this method on as large or small a tank as you like. Rather, it is a function of using an approach that works—and avoiding one that does not. In addition to using this new technology you will also have to exercise a bit of patience. Impatience is one of the most difficult attributes to overcome in terms of fishkeeping, as everyone wants to see the tank finished and have the feeling of being successful immediately.

Realistically, it can easily take 6 months to stabilize a tank and probably another 6 months for a new aquarium to be completely established for the long haul. There is a saying that “nothing good ever happens fast in a marine tank.” This holds true more often than not. Of course, a new marine aquarium can be interesting and viewable in short order, but it will likely take some months before it starts to become the thing of beauty you may be imagining. (For anyone who insists on overnight results, I would suggest hiring an experienced professional to install and maintain your aquarium. This will not, however, be inexpensive.)

Years of Reward

For the true home aquarist creating his or her own system, I think it’s very important that you see this project as more than a few weekends of diversion. A tankful of fishes may be less demanding than a dog, cat, or horse, but the same sense of responsibility for the well-being of a live animal ought to apply. If you aren’t willing to make a long-term commitment to the success of your marine aquarium and the consistent care of its living inhabitants, this is not the hobby for you. On the other hand, if you find the attraction of marine fishes and other organisms irresistible, this could become a lifelong passion as it has for so many others. Watching fishes is a time-tested stress reliever, and many of us find the rituals of feeding and maintenance relaxing and satisfying.

To be a successful marine aquarist demands at least a modest investment of your time, intelligence, money, energy, and creativity. In return, it allows you to exercise any pent-up desires you may have to be a marine zoologist, biochemist, hydraulic engineer, plumber, nutritionist, and/or aquascape designer. Many marine aquarists also find that their aquarium opens a feeling of direct connection to farflung coral reefs and exotic tropical ecosystems, leading many to take up diving, snorkeling, and adventure travel. I can almost guarantee that a marine aquarium will keep you challenged and continually exposed to new ideas and fresh insights for as long as you stay involved. In my own case, after several decades of setting up and observing aquariums, I still consider myself to be on the steep upward slope of my own personal learning curve. I enjoy experimenting and dealing with scientific challenges where there are often more mysteries than answers.

Entering the world of saltwater aquariums can be both exciting and the start of a personal voyage. I hope this book eases the passage and helps steer you toward the success and unique personal satisfaction that creating a healthy, vibrant marine aquarium can bring.

—Michael S. Paletta

From: The New Marine Aquarium